On the Poverty of Christmas

A Nativity sanitized of its social and political context is devoid of incarnation. Insofar as the phenomenon of Christmas is "Incarnate," it includes all the dung and flies that accompany our fleshly existence.

When we say that Jesus "condescended" at Christmas to become human and that God, thereby, identifies with us in this way (as, that is, a human being), we impoverish the event if we relegate this to metaphysics alone. This would deny the phenomenon of Christmas – the comfortably-uncomfortable Nativity scenes that we so love to depict in our yards and on our Christmas cards (though always sans the dung and flies).

Indeed, a Nativity sanitized of its social and political context is one wherein the accoutrements we so cherish – the manger, the hay, the braying calf, the adoring shepherds – are little more than sentimental trinkets, ultimately arbitrary and serving no purpose but to punctuate this "holiday season" with some distinct and differentiated story not unlike the other moral fables that occupy our ears and eyes every December (think Frosty the Snowman or Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer).

The fact is this: Jesus of Nazareth was born into poverty.

The story of Jesus' birth, as we have it, tells us that his mother Mary had no nursery for her newborn, no family nearby, and no way even to go home. She labored and delivered "on the road," as it were. The Gospel of Matthew – and the apocrypha – report that Jesus and Mary spent the first years of his life as political refugees in Egypt, fleeing the mad king of his homeland who had sentenced him to death. Back in Nazareth, Jesus' family was certainly unlike any other and (if my experience with people has taught me anything) would have been the subject of much gossip. Did Mary's neighbors ever really believe, or even understand, her outlandish tale? A baby with no human father? Did she even tell them this story, or did she live with a lifelong secret? And of course, Jesus' nation of Israel was held captive by an empire far greater than it could ever hope to be – his people were, for all intents and purposes, enslaved.

No, this isn't about trying to shoehorn Jesus's story into some hyper-political mold (Jesus the "undocumented immigrant," or whatever). Insofar as Jesus genuinely identifies with us (again, in more than a merely propositional or metaphysical way), this is about admitting the truth of who we are. Few of us know a truly "normal" family (and of course, such is certainly not the "norm"), and we clearly aren't saved by such circumstances (indeed, this would be exactly contrary to the Gospel, let alone to millions of real-life examples). St. Paul says that Jesus "sympathize[s] with our weaknesses" – not our strengths or our glory. Most of us are wanderers of some kind, not sure exactly where we belong and often discontent with the place and station wherein we find ourselves. And, I insist, if we believe that we are not wanderers, we probably haven't thought hard enough about our true life station. We may not be running from a jealous and evil king, but we are probably running from something.

Another fact is this: We need deliverance, and we should look for it eagerly.

I think we ought to focus, in this season, on mitigating the things that keep us from doing that – our sin, our suffering, our ego, and especially all the comforts that make it hard to actually believe, deep down, that we, personally, need "deliverance." Indeed, where is the joy in the birth of Jesus if we do not need him, somehow? We can't have our cakes and eat them, too. But if, in this particular season and at this particular moment, we find ourselves well-fed, secure, and feeling wholly unthreatened by things physical or spiritual, then we should, at least, learn to identify better with those for whom deliverance is not an abstraction: the poor, the displaced, the refugee, the unjustly treated, the homeless – those who know, in their bones, that they cannot save themselves.

(I think, in this vein, of a friend who was murdered some years ago – an injustice that cannot be undone, and one that, it seems now, will by some dark magic evade the almost-weightless hammer of any earthly justice. Here, deliverance is and will always be needed. To my shame, I sometimes forget about this.)

Jesus is the Christ, who is the Logos, who is the Incarnate God. This happened – and continues to happen – amidst a particular set of circumstances, and they are nothing like what we should expect from the arrival of a "King." Insofar as these humble circumstances fail to surprise us, we've forgotten the meaning of this story, and it even ceases, I think, to be "Christmas."

I shared this quote last Christmas. From Sergei Bulgakov:

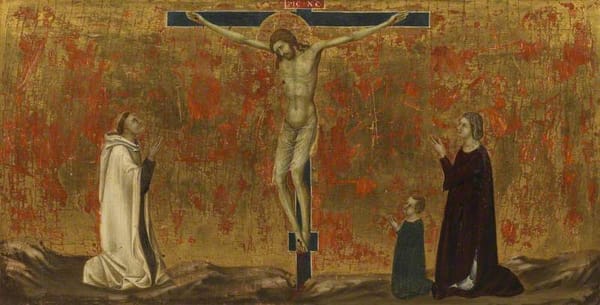

"Christians know that the sign of God is powerlessness in this world – a poor infant in a manger. And there is no need to gild the manger, for a gilded manger is no longer Christ's manger. There is no need for earthly defense, for such defense is superfluous for the infant Christ. There is no need for earthly magnificence, for it is rejected by the King of Glory, the infant in the manger.

But there is a need for the authentic revelation of the God of Love. There is a need for the image of all-forgiving meekness, praying for His enemies and tormentors. There is a need for the image of the way of the cross to Christ's Kingdom, to defeat evil by the triumphant self-evidence of good. There is a need for the image of freedom from the world.

And powerless, we are powerful. In the kingdom of this world we desire to serve the Kingdom of God. We believe in, call, and await this Kingdom. For we have come to know the sign of the infant in the manger – power in powerlessness, triumph in humiliation."

If we can assume this humble posture successfully, I think we can see just how important – how necessary – are the complicated and unsettling circumstances of Jesus' birth. We can embrace this phenomenon of poverty and place ourselves, somehow, within it, and thereby understand the Incarnation better. And we can see deliverance where we might otherwise find no obvious demand for such within our secure hearts and warm homes.

My neighbor has a sign on his lawn today: "Keep Christ in Christmas." What does this mean? Certainly this entails an awareness of the metaphysical meaning of Christmas. But that's only part of the story, and one wholly incomplete (indeed, even incoherent) on its own. To acknowledge only a metaphysical sequence, stripped of its phenomenal and historical material, is to arrive at something with no organic bearing on us at all, except insofar as we imagine ourselves capable of imputing meaning to the poor manger setting (as if we were God), rather than receiving meaning from it.

A "Christ"-mas, if we are actually serious about that, is as social and political as it is metaphysical. Jesus was born in a cave, with no human father, to a nation enslaved, while hiding from a mad king. There is no Incarnation apart from these facts. We celebrate a very specific manger.