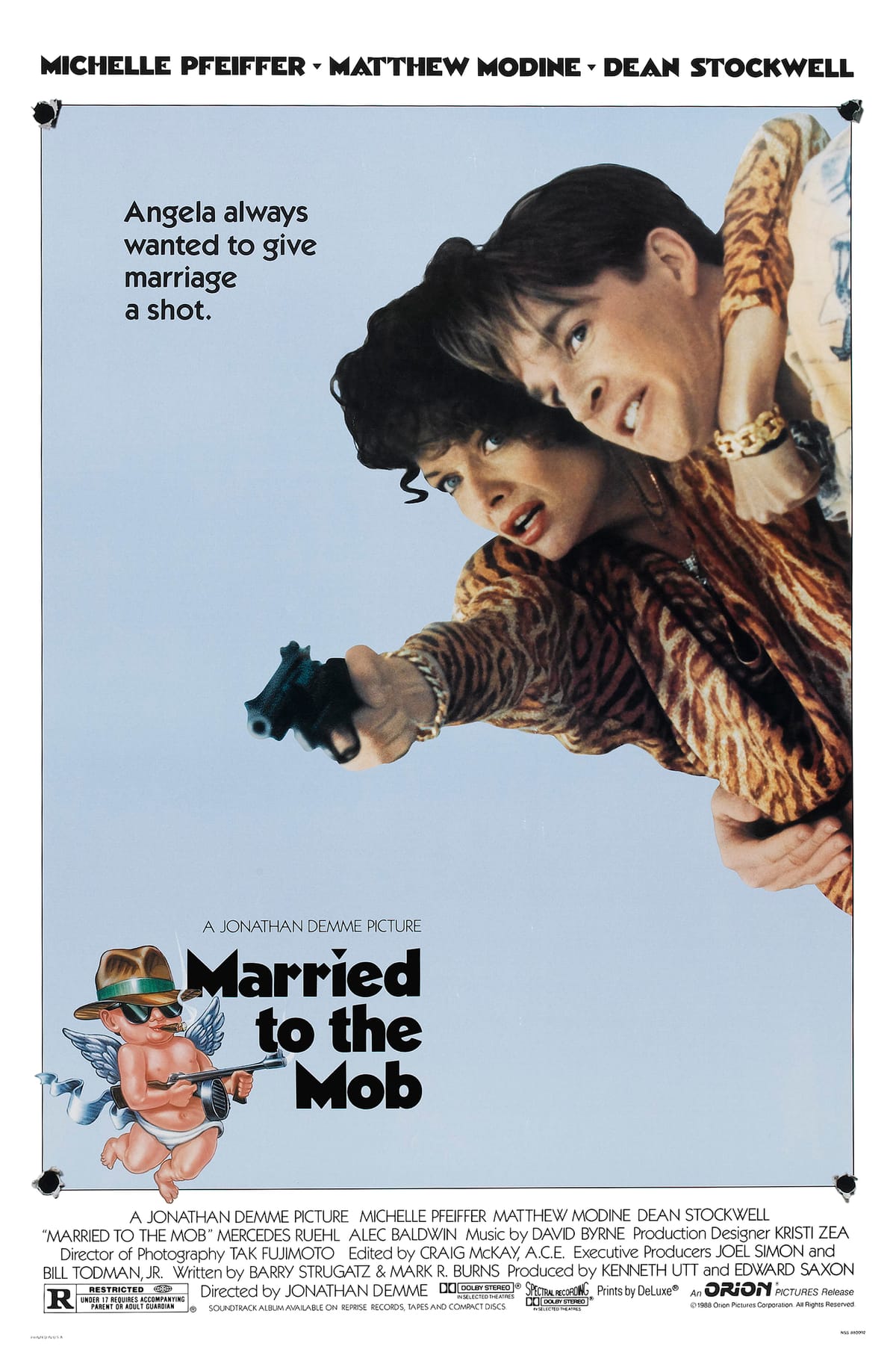

Married to the Mob II: America Settles?

An opinion piece in Vanity Fair wants to give us rubberneckers—or, you know, trainspotters, depending on which side of the tracks we may be standing (there can be only two, right?)—an apter set of historical precedents to talk about the M.O. of really existing Trumpism over against the spectral fever dreams of a decade of Trumpamania/melancholia.

This article reminds me of Mark Fisher’s elaboration on the mob analogy for politics and business in our age—if there’s a difference, it’s hard to spot, isn’t it?—in Chapter 5 of Capitalist Realism, contrasting mafia as portrayed in Coppola’s “Godfather” or Scorsese’s “Goodfellas” with the liquid modern and technocratic model of criminal enterprise shown in Michael Mann’s “Heat.” Fisher highlights how this corresponds to the Fordist to post-Fordist shift into a financialized and information-based economy. Rick Wartzman’s book The End of Loyalty: The Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America shows how this played out more broadly in corporate culture beyond real estate specifically. Also needed is an account of how identity politics—of the left or right—is a reconfiguration of New Deal Fordist corporatism’s representation of vocational groups to suit precisely these post-Fordist conditions. Wiarda’s Corporatism and Comparative Politics (1996) remains among the few treatments I’ve seen. Is there anything more recent that could enrich or update this account?

Trump’s style—though not always his substance, I am convinced, possibly contrary to this article’s author—is out of step with post-Fordism, which has ruled the roost (now a mobile digital henhouse of precarity that can be disassembled and reassembled anywhere) for almost half a century already. This is the basis of his appeal—as well as that of Bernie Sanders—to those nostalgic for the former. Much of the Trump I volatility of personnel and policy arose directly from the lived contradiction of operating with a retro Fordist loyalty mentality in a post-Fordist world. This is what most of us really mean—but can’t find the concepts ready to hand—when we are persuaded to sound the alarm for or against “fascism” as well as “socialism”: something both had in common with New Deal “liberalism” and Catholic “personalism” or the compromise of the two, Christian Democracy. I wish we could bring back the ornery union bosses and humanist Bildung, not just the landlords! The trouble is, we are stuck in passive consumer mode. I doubt mass mobilization is ahead.

Sam Tanenhaus has recognized a real dynamic and is right to note its resemblance to the charismatic FDR model that, after culminating in LBJ’s strong-arming for civil rights, exhausted itself into unsexy routinized bureaucracy. ST declines to speculate about what’s coming after the marvellous bastard arc where Trump “has brought Tammany-Mob rule to the pinnacle of American politics and power.” “Like FDR before him, Trump has blundered into error. Time and again the courts, including the Supreme Court, have told him to desist, though they have no power of enforcement. There has been wreckage all along the way.” Now, my sceptical instinct tells me that all the Don’s men and what too few of them are conscious of as a visionary project requiring a massive economic overhaul—e.g., bringing manufacturing back for real, which involves massive spending rather than tax and service cuts—means their retro-Fordist project is simulacral at best and already recuperated by a neoliberalism reports of whose death are exaggerated. What say you, reader?

Some excerpts from Fisher, Chapter 5: is Trump one or the other or a mix of both? Let us know in the comments:

“‘A guy told me one time’, says organized crime boss Neil McCauley in Michael Mann’s 1995 film Heat, ’Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner’.”

“In Heat, the scores are undertaken not by Families with links to the Old Country, but by rootless crews, in an LA of polished chrome and interchangeable designer kitchens, of featureless freeways and late-night diners. All the local color, the cuisine aromas, the cultural idiolects which the likes of The Godfather and Goodfellas depended upon have been painted over and re-fitted. Heat’s Los Angeles is a world without landmarks, a branded Sprawl, where markable territory has been replaced by endlessly repeating vistas of replicating franchises. The ghosts of Old Europe that stalked Scorsese and Coppola’s streets have been exorcised, buried with the ancient beefs, bad blood and burning vendettas somewhere beneath the multinational coffee shops.”

“McCauley is no mafia Boss, no puffed-up chief perched atop a baroque hierarchy governed by codes as solemn and mysterious as those of the Catholic Church and written in the blood of a thousand feuds. His Crew are professionals, hands-on entrepreneur-speculators, crime-technicians, whose credo is the exact opposite of Cosa Nostra family loyalty. Family ties are unsustainable in these conditions, as McCauley tells the Pacino character, the driven detective, Vincent Hanna. ‘Now, if you’re on me and you gotta move when I move, how do you expect to keep a marriage?”

“Hanna is McCauley’s shadow, forced to assume his insubstantiality, his perpetual mobility. Like any group of shareholders, McCauley’s crew is held together by the prospect of future revenue; any other bonds are optional extras, almost certainly dangerous. Their arrangement is temporary, pragmatic and lateral – they know that they are interchangeable machine parts, that there are no guarantees, that nothing lasts. Compared to this, the goodfellas seem like sedentary sentimentalists, rooted in dying communities, doomed territories.”