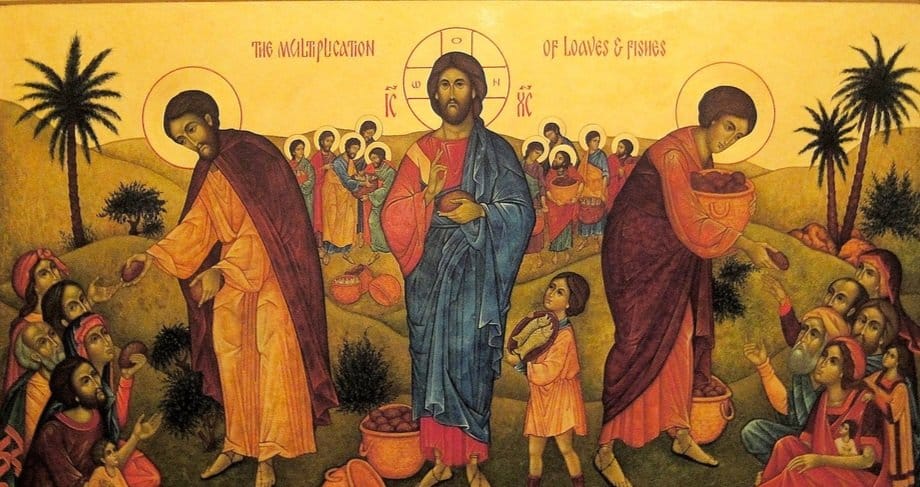

Deity and Dismemberment: Dionysus' Death and Christ's Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes

Christ's act of the feeding of the multitude is the sole miracle referenced in all four canonical gospels. The Apostle John calls the phenomenon a sēmeion—a "sign"— indicating to his reader the parabolic, symbolic nature of this particular scripture. Relying primarily on Olympiodorus’ allegorization of the mythological dismemberment of the Cretan deity, Dionysus Zagreus, in this short article, we will offer a solution to the problem presented by Christ's rich, symbolic "sign."

In John 6, the Apostle relates that, at the time of Passover, 5,000 of Jesus' disciples followed him into the mountains of Galilee. That he might feed the hungry multitude, with only two fish and five loaves of barley bread, Christ performed the miraculous act of multiplying the meager rations, so that all those who were present were able to participate in the marvelous meal. So plentiful was his multiplication, in fact, that there were even portions remaining, which had to be gathered up that none might be left to waste.

Insofar as both the two fish and the five loaves are representative of Christ himself, the Christian savior's miracle of feeding the multitude is in essence a symbolic act of divine dismemberment.

Firstly, the two fish signify Christ as being symbolized by the zodiacal sign of Pisces, wherein the sun—the cosmic viceregent of the transcendent Monad or One on the sensible plane—rose on the vernal equinox in first century (per the precession of the equinoxes), just nine months prior to the birth of Christ following the winter solstice. As the sun slid into the astrological 'sign of the fishes,' the Christian savior was in truth at that same time being conceived.

Secondly, the five loaves also signify Christ as symbolized by the Old Testament shewbread, which consisted of twelve loaves of barley placed on the table of offering in the Temple of Jerusalem. Precisely five of these loaves, we learn from the Mishnah, were specifically allotted to the Jewish High Priest (Yoma). As both the "bread of offering" (Luke 6:4 NAB) and the "great high priest," (Heb 4:14 NIV) Christ happens to be identified with both these. In distributing said highly symbolic foods to the hungry crowd, moving parabolically 'from the One to the many,' Christ is in effect allegorically dismembering and distributing himself to the multitude.

From the Egyptian Osiris, to the Cretan Dionysus, to the Thracian Orpheus, divine dismemberment was a common motif associated with a number of deities connected to the ancient mystery rites and initiations. In feeding the multitude with foods that foreshadow the mystical meal of Christ's last supper—and thus the Eucharist itself, wherein worshippers partake of the Lord's very flesh and blood—Jesus has aligned himself with a long lineage of mythological predecessors who, from a Perennialist or even from Traditionalist Christian perspective, may be said to find their ultimate fulfillment in the physical Incarnation of the Word of God.

Christ's miracle was therefore one type of a much larger arche of divine dismemberment.

The allegory of divine dismemberment attempts to answer the ontological question of how the Monad transitions into becoming the multitude. For instance, the late Neoplatonist, Dr. Algis Uždavinys, wrote in his treatise, Orpheus and the Roots of Platonism, "the dismemberment of Dionysus (that partly follows the Osirian pattern) represents the proceeding of the One into the Many" (p. 70). According to Olympiodorus, the last of the so-called pagans to maintain control of the Platonist tradition following Justinian's 'Decree of 529 AD,'

Zeus is succeeded by Dionysus, whom, they say, his retainers the Titans tear to pieces through Hera’s plotting, and they eat his flesh. Zeus, incensed, strikes them with his thunderbolts, and the soot of the vapors that rise from them becomes the matter from which men are created. [Our] bodies belong to Dionysus; we are, in fact, a part of him, being made of the soot of the Titans who ate his flesh. [Our soul] lives by the ethical and physical virtues, symbolized by the reign of Dionysus; hence he is torn to pieces, [...] and the Titans chew his flesh, mastication standing for extreme division, because Dionysus is the patron of this world, where extreme division prevails because of 'mine' and 'thine.' In the Titans who tear him to pieces, the ti ["ti" in "titan"] ('something') demotes the particular, for the universal form is broken up in genesis, and Dionysus is the monad of the Titans.

As Olympiodorus says, "Dionysus is the monad of the Titans." The wine god's dismemberment by the pre-Olympian gods thus serves as a metaphorical device communicating the ontological process by which the Monad became the multitude. Furthermore, according to the Neoplatonists of late antiquity, we are all in effect 'members' in the body of the dis-membered god.

In regard to Christ, Paul preached an identical message to the Romans: "So we, being many, are one body in Christ, and every one members one of another" (Rom 12:5) And, to the Corinthians, he said similarly, "Know ye not that your bodies are the members of Christ?” (I Cor 6:15 KJV) "For as the body is one, and hath many members, and all the members of that one body, being many, are one body: so also is Christ" (I Cor 12:12 KJV). "Now ye are the body of Christ, and members in particular" (I Cor 12:27 KJV).

Moreover, to the Ephesians and Colossians, Paul wrote of Christ as the head of this mystical body: "And he is the head of the body, the church," (Col 1:18 KJV) and "Christ is the head of the church: and he is the saviour of the body" (Eph 5:23 KJV).

Ergo, just as Dionysus signified the Monad for Olympiodorus, so too does Christ symbolize the Monad for Paul. In this Monad, "'mine' and 'thine'" participate, and it is in this Monad that we ultimately "live, and move, and have our being" (Acts 17:28 KJV)

In this same context, Dr. Uždavinys discusses Plato's notion of anamnesis or divine 'remembering,' which the Lithuanian Neoplatonist brilliantly interprets as an example of "the re-membering of the Osirian body (i.e., the restoration of the members of the dismembered body)," per Uždavinys. Remembering one's source is in effect re-membering the dismembered body of God. In Christianity, anamnesis is specifically associated with the sacrifice of the Eucharist or Mass, having its origin in Christ's command at the last supper, τοῦτο ποιεῖτε εἰς τὴν ἐμὴν ἀνάμνησιν, "this do in remembrance of me" (I Cor 11:24 KJV).

In coming together as the mystical body of Christ, to celebrate Communion, the Christian church essentially "re-members" the "dismembered body" of the Christian savior.

Christ's miracle of feeding the five thousand is indeed a sēmeion—a "sign"—and what it signifies is the solution to the ontological problem of how the "One" becomes the "Many." Olympiodorus' commentary on Plato's Phaedo provides the proper philosophical key for reading that "sign." And, as we have seen, Paul's various letters would appear to reinforce such a reading.

In a way, it is fitting that Christ's act of feeding the multitude happens to be the one miracle in which all four of the gospels participate.