Beholding Calvary: On the Phenomenological Poverty of Penal Substitution

The model of penal substitution occludes the event of the Crucifixion with abstract mechanism. But the phenomenon of Calvary offers and compels something more.

"The wrong way of seeking. The attention fixed on a problem. Another phenomenon due to horror of the void. We do not want to have lost our labour. The heat of the chase. We must not want to find: as in the case of an excessive devotion, we become dependent on the object of our efforts. We need an outward reward which chance sometimes provides and which we are ready to accept at the price of a deformation of the truth. It is only effort without desire (not attached to an object) which infallibly contains a reward. To draw back before the object we are pursuing. Only an indirect method is effective. We do nothing if we have not first drawn back. By pulling at the bunch, we make all the grapes fall to the ground."

~Simone Weil

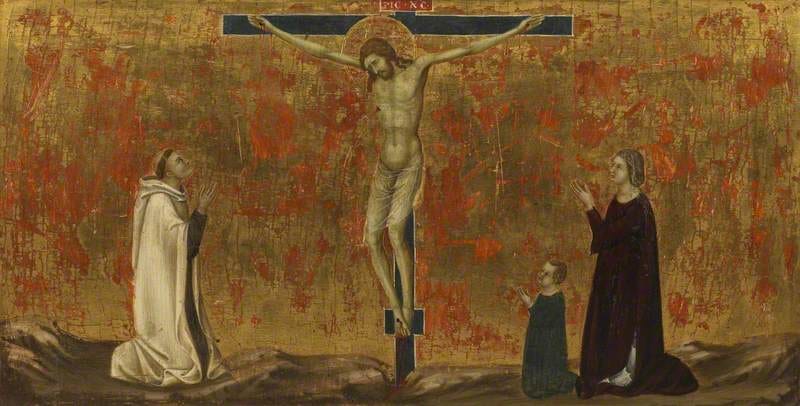

The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ is the center of Christian faith — not merely as theological proposition, but as historical rupture and visual confrontation. It is where everything stops, where meaning floods in and language runs out, where the divine becomes most visible precisely in its death.

Among the many interpretations of this event, penal substitutionary atonement (PSA) — the doctrine that says God poured out His divine wrath on Jesus as humanity's substitute — has commanded special authority in Reformed Protestant traditions. In this model, a guilty race deserves punishment but is spared the direct wrath of God by the intervention of an innocent representative of the race. The innocent suffers, yes, and the guilty are spared, but divine justice still finds its level because of the sinless nature of its victim – a "spotless lamb" – and all is made whole again. These mechanics are clean and primed, prima facie, for an elegant and analytically robust articulation. At its best, the theory arises out of an earnest commitment to uphold both the gravity of sin and of God's righteousness.

But something subtle happens in this telling that has dramatic consequences for how we understand the event – something that reveals itself only under careful, reflective scrutiny. That is, PSA doesn't simply interpret the Crucifixion, but systematically relocates its locus of power and significance. The theory places the salvific meaning of Calvary somewhere beneath or behind the visible event, as if what actually transpired before the disciples and within Christ's own consciousness cannot, on their own, bear the weight of redemption. It is as if the cries, the blood, the abandonment, the forgiveness (those elements rooted in history and embodied experience) achieve cosmological significance only when interpreted through very particular metaphysical scaffolding and strictly juridical analogy.

This constitutes the phenomenological poverty of a PSA heuristic – its structural impulse to evacuate the concrete event in favor of an abstract mechanism. The problem is not that PSA thinks too much about the Cross, but that it trusts too little in what we witness at Calvary.

The Phenomenological Method: Encountering What Gives Itself

Phenomenology, in the tradition kicked-off by Edmund Husserl and developed through Maurice Merleau-Ponty's "embodied philosophy," calls us to rigorous attention to reality as it is presented to us – to (attempt to) encounter phenomena as they give themselves, before theory intervenes to "explain" them. It demands what Husserl called the epoché – a methodical bracketing of assumptions that allows a thing itself to appear in its full presence (this being, of course, an ongoing and never-completed task).

This phenomenological reduction is not mere passivity, but an active discipline of laborious receptivity. It asks: What is actually given here? What presents itself before interpretation begins its work? What would we see if we could suspend our theoretical frameworks long enough to let the phenomenon speak?

Applied to the Crucifixion, this method beckons us to attune and re-attune ourselves to what is concretely shown (for us, through the Gospel texts): a poor Jewish man condemned by Roman imperial authority and Jewish religious establishment alike; tortured flesh hanging on splintered wood; a cry of divine forsakenness that splits the afternoon air; blood pooling in Palestinian dust; a mother's vigil of grief; Joseph's unused tomb. These are not ornamental details or narrative incidentals – they constitute the form and substance of the event itself (what grounds have we to confidently assert otherwise?).

In Christian confession, these terrible particulars are not merely tragic accidents of history. They, themselves, are proclaimed as redemptive. The phenomenological question becomes: How does this visible suffering save? Not what invisible mechanism might explain salvation, but how does salvation show itself in this concrete death (and, later, resurrection)?

To approach the Cross phenomenologically means saying that this is what salvation looks like – not an abstraction requiring some definite or authorized decoding or cosmic formula demanding assent, but a historical moment dense with presence, both unbearable in its totality and somehow sufficient in what little we might grasp of it.

Jean-Luc Marion's analysis of saturated phenomena provides crucial insight here. Unlike ordinary phenomena that can fit more comfortably within our conceptual frameworks, saturated phenomena give more than any theory can contain. They overflow every attempt at adequate representation – he uses, as one example, our encounter with the face of another. "The face is given to me only in the measure that it withdraws from any objectifying gaze," Marion writes, "and precisely in this withdrawal it gives more than any object could: it gives the other himself, in the mode of his call." But it's the Crucifixion that exemplifies this saturation perfectly: it exceeds every theological model, cannot be diagrammed without remainder, and resists reduction to any single interpretive scheme (this is, arguably, historically demonstrable).

Marion identifies several types of saturation. The Cross participates in all of them: as historical event (saturated in quantity – infinite implications flowing from a single afternoon), as embodied suffering (saturated in quality – no concept captures the reality of that pain), as absolute gift (saturated in relation – grace that creates rather than responds to conditions), and as icon of the invisible God (saturated in modality – the impossible possibility of divine vulnerability).

This saturation explains why the Cross continues to generate new theological insights across centuries. It gives more than any single model (including PSA) can receive, let alone distill. The phenomenon keeps exceeding the theory.

How PSA Evacuates the Event

In light of this, insofar as PSA is deemed to be the most authoritative (or, the "correct") interpretation of the Crucifixion, it performs a systematic evacuation of phenomenological content, replacing the concrete event with an invisible transaction. Under this account, what mattered most (and forever) was never what anyone actually witnessed – neither the disciples' terror, nor the centurion's recognition, nor Christ's own experience of abandonment. These were "accidentals" that may as well have happened some other way without any consequence for the "atoning" work completed on Good Friday. What mattered was the unseen transfer of guilt and punishment occurring in divine consciousness and accessible to us only through derivative and analogical apparatus.

Consider the interpretive distortion this requires – a kind of theft of immediacy. The Gospels narrate death, not transaction. They describe grief, not divine bookkeeping (even as they hint, some more than others and some hardly at all, at the cosmic significance of Jesus' death). They show forgiveness emerging from the very event of Crucifixion ("Father, forgive them") – not from some posterior divine decision based on satisfied justice. Yet PSA encourages us to look beyond these surface phenomena to access the "real" meaning hidden behind appearances – to allege to know more about (and glean more from) what really happened, so to speak, than did those who physically loved Jesus and witnessed the Crucifixion firsthand.

This creates a phenomenological smoke-and-mirrors: the actual event becomes merely symbolic of its own meaning, hollowed out by insipid abstraction. The Cross functions as signifier pointing away from itself toward an invisible signified. What saves is not the concrete death we can witness, but the abstract transaction we must infer.

The Political and Pastoral Costs of Evacuation

When PSA crowds out other interpretations of the Crucifixion, Christian faith risks a fundamental transformation – from encounter with a saturated phenomenon to intellectual assent to a theory. The Cross no longer functions as the place where salvation unfolds but becomes merely the accidental occasion for something that happens substantively only elsewhere – in divine consciousness beyond the pale of raw human experience.

This evacuation carries profound political implications. The scandal of Calvary – that imperial violence murdered God, that religious authority collaborated in deicide, that divine power shows itself through absolute vulnerability – is domesticated into a story about divine justice satisfied. The Cross becomes comfortable, even necessary for divine order, rather than God's definitive judgment on human systems of domination. This instrument of torture is transformed into something sentimental and, notably, typically deprived of the human corpus that lends it any relevance.

(An interesting follow-up here: according to PSA's logic, what is to say that Jesus might as well have killed himself and "accomplished" the same result? If God demanded spilt blood in order to balance the ledger of divine justice, would Jesus' ritual slaughter on the temple altar not have sufficed? Is this an acceptable perspective?)

Pastorally, this evacuation of the phenomenon tends to cultivate a spirituality that is needlessly distanced from our immediate, sensory experience of life. When PSA is treated as the definitive explanation of the Crucifixion, immediate and impulsive responses to the horrors of, say, human torture and social injustice are discouraged. A recoil at divine violence, solidarity (let alone identification) with the suffering of the innocent man, any intuitive sense that the Crucifixion itself reveals rather than obscures divine love – these impulses become naïve or insufficiently theological in the face of PSA, often inviting correction by a more abstract interpretive grid in order to offer any value in that dialogical context. Over time, the crucifix itself risks becoming suspect—not a window into divine love or a picture of God's co-suffering with us, but an image to be looked past or beyond, lest the gaze linger too long on what is meant to be merely symbolic. Indeed, in some Reformed Protestant traditions, to gaze upon the crucifix is literally verboten.

Moreover, the logic of penal substitution tends to graft itself into Christian self-understanding in totalizing ways. If God's love requires violent satisfaction and divine forgiveness depends on sufficient punishment being inflicted elsewhere, then human forgiveness likewise becomes conditional on proper retribution. The Cross, rather than revealing the gratuitous nature of grace, seems to demonstrate that grace always has a price (just one that someone else has paid). Beyond the nature of grace, it also chips away at the phenomenological density of life itself – the sweat and tears of Gethsemane, the communal lament at the foot of the Cross, the everyday agonies of betrayal and loss that echo Calvary in every human story. By privileging the unseen mechanism over the visible rupture, PSA not only distrusts the event's power to save, but also impoverishes our lived world, rendering human phenomenality a "shadow play" – devoid of its inherent weight and its capacity to reveal the divine precisely through the cracks of finitude and flesh.

In this way, the theory betrays not just the Cross, but the very humanity it claims to redeem, often leaving its adherents with a salvation that feels, despite its elegance, empty – characterized fundamentally by "forensics" that are alleged to function, in a sense, prior to (and even devoid of) encounter, estranged from the textures of human life, with only symbols instead of sacraments.

Toward Phenomenological Faith: Attending to What Is Given

To critique PSA phenomenologically in this way is not to deny either sin or redemption, or even that such a model (or any model, for that matter) isn't useful on some margins. The problem is not theory as such, but when theory becomes totalizing and folded back onto its phenomenal source material – that is, when it attempts to contain and master the phenomenon and forecloses any attempt at speculative contemplation. Rather, it is to ask whether salvific meaning entails the evacuation of concrete "earthly" phenomena or might instead emerge from more faithful attention to the circumstances and conditions out of which the Crucifixion arises as an intelligible event. It is to ask, alongside Marion: If it "saves" at all, what if the Cross saves precisely as phenomenon? What if its salvific power lies not behind appearances but in its very showing? What if the event's excessive giving – its saturated self-presentation – is itself the form of divine grace?

Consider what the Cross demonstrates when approached without the mediating theory of penal substitution – divine solidarity with victims of injustice; perfect love's refusal to return violence for violence; the Creator's willingness to experience the full consequences of creaturely rebellion without abandoning the relationship; forgiveness spoken from within suffering rather than after its resolution; life emerging from death not through magical reversal but through the kind of self-gift that creates new possibilities in the very moment of apparent defeat; silence (even capitulation) before an empire of lies that, in this absolute incompatibility, affirms the enduring reality of the good it opposes – "the best self-attestation of the Good is its defenselessness in the face of the power of evil," writes Sergei Bulgakov.

None of these various meanings require invisible transactions or abstract juridical frameworks. They emerge, more or less and to varying degrees, from careful attention to what actually happens in the event itself. They trust the saturated phenomenon to carry its own salvific weight and continually give rise to something ever greater. Marion writes:

[A]t the time of the Transfiguration, where the evidence of Christ's divine glory shone forth so much that his clothes became "intensely white, as no fuller on earth could bleach them," when, that is, the intuition surpassed what the world permits and tolerates, they all "became exceedingly afraid," so much so that Peter could only chatter about three booths, because "he did not know what to say." Standing before the crucified, too, the intuition, this time without glory, but sinister and prosaic, nevertheless allowed no one to say anything appropriate – no one understood what they were nevertheless all seeing, to the point that, at the cry, "Elie, why have you abandoned me?" they recognized neither "my God!" nor the words of Psalm 22, but heard only the name of the prophet Elijah.

...

Standing before the Christ in glory, in agony, or resurrected, it is always words (and thus concepts) that we lack in order to say what we see, in short to see that with which intuition floods our eyes. When he comes among us – though he comes, or rather precisely because he comes –, we, who are his own people, cannot "grasp him, understand him." God does not measure out stingily his intuitive manifestation, as if he wanted to mask himself at the moment of showing himself. But we do not offer concepts capable of handling a gift without measure and, overwhelmed, dazzled, and submerged by his glory, we no longer see anything. ... What is more, the miscomprehension even appears inevitable – so much does the inadequacy of our concepts to the factual intuition of Christ result directly from the incommensurability of the gift of God to the expectation of men. What is there to say?

This suggests a different model of theological understanding – one that seeks not to explain the Cross definitively, but to receive it more fully, even unto intuition. Such theology would function more like contemplative practice than like theoretical construction. It would cultivate capacities not for forensics, analytical rigor, and balancing ledgers, but for sustained attention – "that attention," writes Simone Weil, "which is so full that the 'I' disappears." It would trust that the Cross continues to yield more meaning than any single theory can contain.

The Catholic imagination, at its most authentic, embodies this phenomenological fidelity. It doesn't rush past the Crucifixion toward explanation. It returns perpetually to the scene itself. The crucifix – Christ still suffering, still present in agony – functions not as symbol of completed transaction but as ongoing confrontation with divine vulnerability. It refuses the consolation of total psychic resolution.

This fidelity appears throughout Catholic tradition. The Stations of the Cross methodically attend to each moment of the passion, lingering over details that pure theory might dismiss as incidental. The physical gestures of liturgy – genuflection, Sign of the Cross, kissing of wounds – engage the body in reception of the mystery rather than mere intellectual assent. The habit of contemplating Christ's physical sufferings in prayer maintains phenomenological contact with the event itself.

Nor is this phenomenological fidelity a modern philosophical retrieval. It is deeply rooted in Catholic mystical and devotional life, long pre-dating phenomenology as a discipline. St. Francis of Assisi (among others) is alleged to have bore the stigmata as a way of dwelling in Christ's suffering, not explaining it. St. Catherine of Siena spoke of Christ's wounds not as symbols but as wells of mercy. St. John Henry Newman emphasized the importance of "real apprehension" over notional assent – insisting that true faith arises not merely from propositional understanding, but from lived, concrete, and often wordless encounter.

These saints and mystics exemplify the Church's long-standing preference for presence over abstraction, for mystery over mechanism. Their witness affirms that attending to what is given, however unspeakable, has always been part of the Catholic path to understanding.

And of course, the Eucharist is Christ's sacrifice experienced anew with each celebration – a version, arguably, of what Mircea Eliade calls religious man's "eternal return" to the primordial, sacred moment wherein we find transcendent meaning and significance (for Christians, the moment of Christ's self-giving). It is to behold the Lamb of God, after all – not to remember or figure.

In this way, Catholic theology resists the reductive mechanics of PSA. Take Aquinas on satisfaction: rather than locating salvific power in transferred punishment, Thomas locates it in the superabundant charity that Christ's human will offers to the Father. The same external event – death on the Cross – but the meaning emerges from what is actually visible (perfect love unto death) rather than from what remains invisible (divine wrath being absorbed).

Or consider the Eastern emphasis on theosis, which continues to dawn with ever more intensity on the Catholic tradition: salvation happens through actual participation in divine life, not through legal fiction. The Incarnation and Crucifixion matter because they create new ontological possibilities, not because they balance cosmic books.

The Catholic practice of contemplating the crucifix models this phenomenological approach. The suffering Christ remains present not as solved problem but as inexhaustible mystery. The wounds stay open, the head still droops, the flesh bears eternal marks of violence absorbed rather than returned. This image teaches a theology of attentive presence rather than explication.

Significantly, the crucifix resists both sentimentality and abstraction. It will not let suffering become merely symbolic, nor will it permit easy comfort. Its presentation holds the viewer in the tension between horror and love, between divine power and vulnerability, between death and life. It refuses resolution – not as a matter of principle, but because Christ continues, like us (his body), to suffer.

This suggests how phenomenological theology might proceed: not by solving the Cross, but by learning to remain present – to attend – to its excessive giving. Not by decoding divine mechanics, but by receiving ever more fully what shows itself in this death (with which we, as co-sufferers, can identify). Not by explaining how it all works, but by bearing witness to the fact that, for so many, it just does.

The Sufficiency of What Appears

The Crucifixion is not salvific despite its visibility, but precisely through it. In every detail, it appeals to the already-unfolding drama of human experience (including the condition of being abandoned by God), prior to any conceptual edifice installed around it. It's a posture, yes, that still requires faith – not every meaningful ingredient at Calvary is immediately relevant to all who look on, and a phenomenological approach possesses no "get out of jail free" card when it comes to reckoning with metaphysical realities.

But at its best, the Catholic imagination, laden as it is with cruciform spirituality and embodied liturgy, engenders exactly this kind of phenomenological faith. It doesn't resolve the scandal of divine vulnerability but holds it open as the form of revelation itself, ever-fertile with new insight and necessarily heedful of the diversity of experiences had by participants in any public phenomenon. It permits the Cross to remain as it came: not as puzzle requiring solution or premature resolution (the world remains broken by the sting of death, after all), but a saturated phenomenon whose excess of meaning continues to give itself to those willing to receive it.

In the end, this may be the most radical claim: that the Crucifixion needs no theory to validate its salvific power because it is itself the visible form of salvation. What hangs on the Cross is not a symbol of redemption accomplished elsewhere but redemption itself – still happening, still present, still sufficient for those permitted and willing to gaze upon it.