The Centre That Can Hold: René Guénon’s The King of the World

The King of the World (Le Roi du monde, 1927) is a short but exceptionally dense work in which René Guénon examines the traditional doctrine of a supreme spiritual centre governing the world. The immediate occasion of the book lies in the early twentieth-century diffusion of accounts concerning Agarttha and a hidden “King of the World,” especially through Ferdinand Ossendowski’s Men, Beasts, and Gods (1922) and the earlier esoteric constructions of Saint-Yves d’Alveydre. These accounts provoked public discussion and scepticism within French intellectual circles, including among figures such as the historian René Grousset and the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain. Grousset approached such materials with the caution of historical scholarship, while Maritain was concerned with the theological dangers of confusing symbolic or mythic material with revelation.

Guénon’s response, however, takes a different form. Rather than entering into disputes over historical accuracy or theological admissibility, he deliberately reframes the issue. The book does not attempt to verify or refute the existence of Agarttha, nor to arbitrate between credulity and scepticism. Instead, it treats the controversy itself as symptomatic of a deeper problem: the modern loss of symbolic intelligence, which leads traditional doctrines to be misunderstood either as literal reportage or as imaginative fantasy. The task Guénon sets himself is therefore principial rather than polemical—to clarify what traditions mean when they speak of a central authority governing the world.

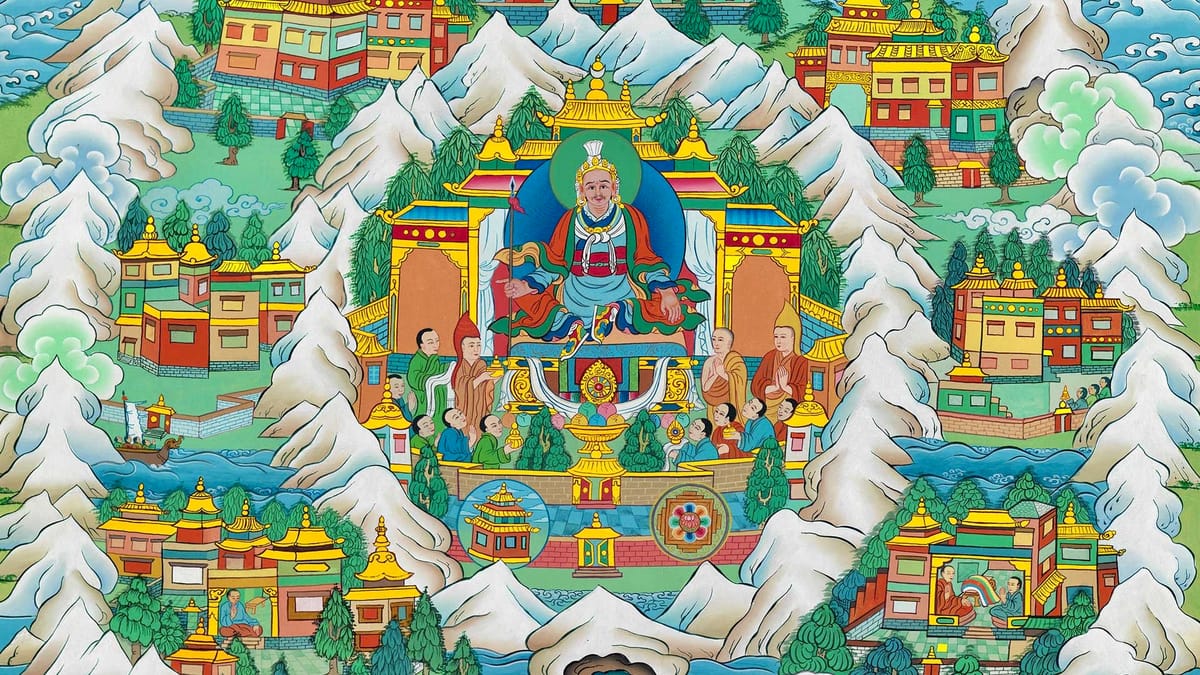

Guénon begins by explicating the title “King of the World,” which he understands not as a political designation but as the symbolic expression of spiritual authority. This authority is identified with the figure of Manu, who in Hindu doctrine represents both cosmic Intelligence and terrestrial legislator, the source of law (dharma) for a given cycle. Manu presides over a terrestrial spiritual centre that preserves primordial tradition and mediates between the divine and human orders. Guénon emphasizes that such authority cannot be reduced to priesthood or kingship taken separately; it implies their conjunction, a unity of sacerdotal and royal functions that later finds Western expression in figures who are simultaneously king and priest.

From this doctrinal foundation, Guénon develops a comparative symbolic analysis across multiple traditions. He examines parallel formulations in Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and Western esoteric sources, focusing on mediating figures and functions that express the same metaphysical structure. Particular attention is given to Melchizedek, who embodies the coincidence of royalty and priesthood; to the symbolism of the Grail, interpreted as an image of spiritual transmission and central authority rather than as a literary romance; and to the city of Luz, associated with immortality and the continuity of tradition. These examples are not treated historically but doctrinally, as diverse symbolic expressions of a single principial reality.

A central distinction elaborated throughout the book is that between the supreme or principial centre and the secondary or subsidiary centres that reflect it within particular historical and geographical conditions. The supreme centre is unique, non-local, and supra-historical; it cannot be identified directly with any earthly place. Secondary centres, by contrast, are legitimate manifestations of the same function, adapted to the needs of specific civilizations or cycles. Guénon stresses that because such centres are more visible, they are easily mistaken for the centre itself—a confusion that underlies both modern literalist readings and sceptical dismissals of traditional symbolism.

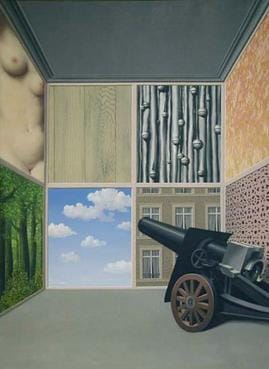

Guénon situates this doctrine within the framework of traditional cosmology and cyclical time, especially the doctrine of the Kali Yuga. In the present cycle, he argues, the supreme centre is withdrawn or concealed, not destroyed. Access to it becomes restricted, and its influence is exercised indirectly through symbols and secondary centres rather than through open authority. This concealment explains the recurrence, across traditions, of imagery involving hidden kings, inaccessible sanctuaries, and subterranean realms. Such imagery, Guénon insists, is symbolic rather than descriptive, encoding the persistence of spiritual authority even when it no longer structures the visible order of society.

The latter chapters of the book turn to the symbolism of centrality in spatial terms. Guénon analyzes the symbolism of the Pole as the immobile axis of the world; the omphalos or “navel of the world”; sacred stones and betyls; caves and subterranean domains; and the language of interiority and invisibility. He also addresses the question of localization, arguing that the centre may be said to have had successive locations corresponding to different cycles, but that such localization is always relative and symbolic, never absolute. The multiplicity of names and representations found across traditions is thus explained as the indication of a single function expressed under diverse forms.

The work concludes by reaffirming that the doctrine of the centre concerns a metaphysical reality, not a historical mystery awaiting discovery. The “King of the World” signifies the enduring principle of spiritual authority that orders the world from within, even when it withdraws from external manifestation. Modern fascination with Agarttha and similar legends is therefore interpreted as a confused response to the loss of direct participation in traditional order. What has disappeared, Guénon argues, is not tradition itself, but the capacity of modern humanity to understand and participate in it through disciplined symbolic knowledge.