Dakpo Tashi Namgyal: Master of Mahāmudrā

Taken as a whole, Dakpo Tashi Namgyal’s teaching reveals a master who articulated Mahāmudrā not as a collection of exalted claims but as a rigorously tested path of recognition, diagnosis, and integration.

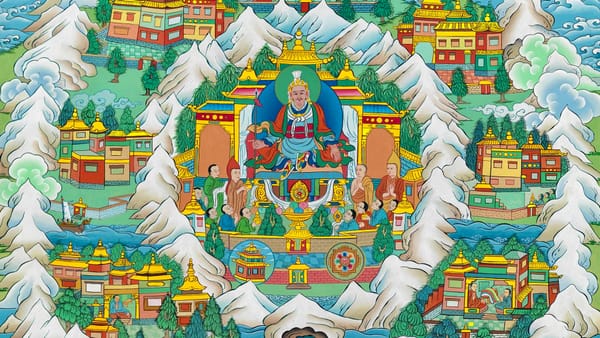

Dakpo Tashi Namgyal (Dwags po Bkra shis rnam rgyal, 1512–1587), often known as Dakpo Paṇchen, stands among the most consequential figures of the post-classical Kagyu tradition. Although surviving biographical information about his life is sparse, the available sources consistently place him at the institutional and doctrinal centre of Dakpo Kagyu Buddhism. He served as abbot of Daklha Gampo, the monastery founded by Gampopa, and lived as a contemporary of the Eighth Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje—whom several traditions identify as having received instruction from him. Trained not only within Kagyu but also in Sakya scholastic circles, Dakpo Tashi Namgyal emerged at a moment when Mahāmudrā required both experiential articulation and intellectual discipline in the face of sustained critique. His enduring importance lies in his ability to unite these demands without collapsing Mahāmudrā into either scholastic abstraction or antinomian mysticism.

This synthesis finds its clearest expression in Clarifying the Natural State (Phyag rgya chen po’i khrid yig chen mo gnyug ma’i de nyid gsal ba), a guidance manual composed at the request of his meditator disciples. From the outset, Dakpo Tashi Namgyal signals that the text will not argue for Mahāmudrā through philosophical polemic but will instead “set intellectual arguments aside” in favour of “the pith instructions of personal experience.” The work is addressed to practitioners marked by deep renunciation, devotion to the lineage, and a sincere wish for liberation rather than status or display. Its opening sections make clear that Mahāmudrā cannot be severed from the broader path: reflection on impermanence, karma, and the miseries of saṃsāra is required so that meditation is not undermined by the eight worldly concerns. Devotion is described as the “head” of practice, mindfulness as its “heart,” and compassion as its outward activity, while premature attempts to teach or “benefit others” without stabilized realization are warned against as subtle obstacles.

The main meditation stages unfold with methodical clarity. Śamatha is introduced as a necessary but provisional support, cultivated with careful attention to posture, breath, and bodily conditions, and accompanied by strikingly concrete remedies for agitation, dullness, and obscuration. Yet Dakpo Tashi Namgyal repeatedly insists that “mere calm is not Mahāmudrā,” and he treats fixation on stillness or clarity as a serious error. Vipashyanā follows not as abstract analysis but as direct investigation of mind, thoughts, emotions, and perceptions. Through examining their arising, abiding, and cessation, the practitioner discovers that these phenomena are “without colour, without shape, without location,” and that their apparent solidity collapses under scrutiny. This investigation establishes the central Mahāmudrā insight that thoughts and perceptions are not obstacles but expressions of mind itself, differing from calm only as waves differ from water.

These insights are sealed through pointing-out instruction, where recognition of the mind’s gnyug ma, its natural and innate state, is confirmed not only in stillness but precisely in the midst of mental movement. One of the text’s most vivid formulations states that when a thought is examined directly, “the vividness of the thought is itself the naked state of aware emptiness,” so that “thought dawns as dharmakāya.” From this point onward, bias toward calm or aversion to thought is exposed as a fundamental misunderstanding. The decisive criterion becomes continuity: as long as “naturally aware mindful presence has not wandered off,” there is no need to suppress experience or protect a special meditative mood.

The second half of Clarifying the Natural State deepens this discipline by focusing on stabilization and integration. Dakpo Tashi Namgyal insists that Mahāmudrā matures only when meditation and post-meditation are “mingled day and night,” extending into activity, emotion, sleep, and even dreaming. When distraction occurs, the instruction is not to dramatize failure but simply “to recognize the natural state, whenever it is remembered,” and even forgetfulness during sleep is remedied by immediate recognition upon waking. Much of this section is devoted to diagnosing subtle sidetracks: blocking off perception, clinging to inconcreteness, resting in indifferent calm, or mistaking lucid thought-free states for completion. “I do not see any of these stances as being the training in Mahāmudrā,” he states bluntly. Practitioners are instead instructed to test recognition by deliberately allowing thoughts and perceptions to arise and examining whether their nature differs from calm—thereby transforming disturbance into confirmation rather than threat.

In the final sections, Dakpo Tashi Namgyal situates Mahāmudrā maturation within the classical framework of the paths and bhūmis, especially through a sober account of nonmeditation. Lesser nonmeditation is marked by the collapse of deliberate effort, yet subtle residues such as “thoughtless nonrecognition” remain; medium nonmeditation brings uninterrupted recognition through day and night, though the most delicate obscurations may still flicker. Only in great nonmeditation does even this final trace dissolve, as “thoughtless nonrecognition dissolves into original wakefulness,” the “mother and child luminosities intermingle,” and dharmakāya is fully realized for one’s own benefit, while the spontaneous activity of the form bodies fulfills the welfare of beings “for as long as saṃsāra lasts.” The concluding verses and colophon underscore the text’s humility and intent: Dakpo Tashi Namgyal apologizes for any shortcomings born of ignorance, dedicates the merit so that all beings may swiftly realize Mahāmudrā, and notes that the work arose directly from repeated requests for a “decisive and reliable guidance manual.”

Taken as a whole, Dakpo Tashi Namgyal’s teaching reveals a master who articulated Mahāmudrā not as a collection of exalted claims but as a rigorously tested path of recognition, diagnosis, and integration. His work implicitly supports a Shentong-compatible understanding of ultimate reality by dismantling adventitious phenomena while allowing the luminous, knowing nature of mind to stand revealed, yet it does so procedurally rather than polemically. For this reason, Clarifying the Natural State has remained a foundational text in Kagyu training: not only a guide to initial recognition, but a demanding manual for making that recognition stable, ordinary, and finally inseparable from life itself.